THE

GUARDIAN

Il

calcio è al cuore di tutto - football is at the heart of everything.

Wise words from the 95-year-old regular at my local coffee bar,

where I stopped off every morning on my way to Sampdoria's

training ground. He meant that in Italy, politics, religion,

business and even relationships were governed by events on the

football pitch.

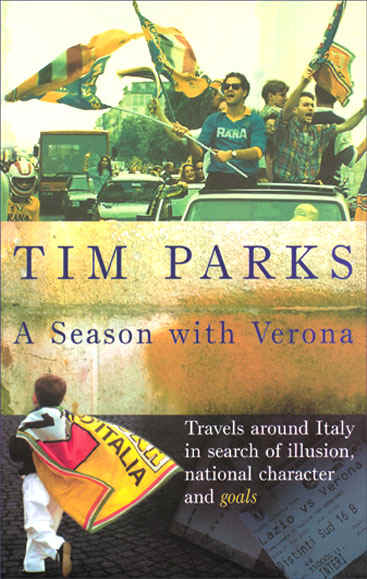

In A Season with Verona, Tim Parks takes us through all

aspects of football in Italy, and examines what it shows us

about the national character. He captures very well the passion,

the bravado, and the downright rudeness, though he

occasionally stretches the truth - in line with the perceptions of

many Italians themselves - as to the advantages that big teams,

such as Juventus, Milan, Internazionale, Roma and Lazio, are

given over their less illustrious adversaries. Historic stories of

match-rigging and biased refereeing decisions have been passed

down through generations of supporters of provincial teams such

as Verona.

The truth is probably less exotic: these clubs have better

players, and are therefore entitled to win more, though it is true

that they also have "bigger" presidents who have more political

clout. But in my four years in Italy I can honestly say that I was

never exposed to any football-related scandal, either against me

at Bari or Sampdoria, or for me at the more powerful Juventus.

But enough of the preaching. Parks's account of a season

travelling with his club in Italy's Serie A gives insights into all

levels of Italian football culture: he infiltrates the club hierarchy,

mingles with the "normal" supporters and, with more passion,

becomes a "Brigate", a member of the club's diehard fans - in

Italy known as the "Ultras". The key to the book is that Parks

gets you involved, while offering different things to different sorts

of reader.

You could enjoy it as an evocative piece of travel writing. I

myself, being of an addictive nature, read it as an Ultra. I had

been long enough away from Serie A not to know where Verona

finished in the league this year and, although I yearned to look

at the back page to find out if they had managed to have a good

season, I resisted the temptation, for fear of ruining the emotions

you feel as you are carried from game to game, looking at the

league table at the end of each chapter. Parks manages to

entwine the seriousness of Italian life with the "seriousness" of

Italian football extremely well. He understands the most

important fact of life in Italy - that without taking football into

account, you cannot understand what passes for normality in

almost every Italian household.

At the provincial clubs such as Verona, all supporters think that

every facet of Italian politics and officialdom is against them.

This goes way beyond the pitch: believing that they are

considered to be the poor relations in life, they rally against

power and money. It is ironic, therefore, that these resentful

people can associate so freely with the players themselves,

revering them as gods, oblivious to the fact that their heroes are

earning money and gaining power that they can only dream of.

I had one taste of this extreme form of hero-worship. Suspended

for a game, ironically against Verona, while I was playing for

Bari, I was invited to watch the game with the supporters in their

curva (end). My dilemma was that the president of the club had

also asked me to sit next to him to watch the game. I made the

tactical decision to spend just 15 minutes with the supporters,

before taking my seat next to the president. For this simple act,

I am now given a hero's welcome whenever I revisit Bari. It made

me a Bari Ultra.

I had the same affinity with the Sampdoria supporters, but could

never really manage it at Juventus. Was this because I didn't

play particularly well or because, at clubs like Juventus, the

supporters are used to winning? Hard to pin down, yet the

warmth shown by the provincials was much greater than that

shown by the big club.

Whether you buy this book as a football fan wishing to know

more about Serie A, or to learn of Italian life and culture, I am

sure you will not be disappointed. By the end of it, you will

understand why my coffee-bar friend was so sure that il calcio è

al cuore di tutto.

David Platt is a former England captain and is currently manager

of the under-21 team. He played in Italy for four years.

|

SUNDAY

HERALD

In many respects, all football hooligans are alike but none, surely, is

as complex as the Italian

hooligan. Tim Parks, who alternates fiction with quirky commentaries on

his adopted country

(Italian Neighbours, An Italian Education) is more sensitive than most

to their peculiar,

puzzling and, bizarrely, endearing characteristics, having spent the 2000-2001

season

following the ebbing fortunes of Verona, a low-hope club, like Hearts or

Partick Thistle, who

are the perennial makeweights of SŽrie A, Italy's premier league.

Early in the campaign, Parks recalls returning by train from Vicenza, where

Verona contrived

a draw against their local rivals. A teenager rushed into the compartment,

slammed down the

window and hurled abuse at the rank of policemen standing only a few yards

away. 'Thugs!

Worms! Turds! Communists! Go f*** yourselves!' he yelled. In normal circumstances,

notes

Parks, if a young man were to do this in the street in a northern Italian

town, he would be

arrested immediately. But on this occasion the police stared back impassively.

'Fascists!

Slavs! Kurds! Bastards! Terroni!'

The youth was nothing if not persistent as he ran through his thesaurus

of insults. Then he

realised his mobile phone -- his telephonino -- was ringing. He pulled

it out of his jacket pocket

and, in a sweet voice, devoid of tension or anger, said: 'No, Mamma, we're

still in the station

at Vicenza. No, we didn't have much homework this weekend. I've already

finished.' As the

train pulled away, he put his hand over the phone and gave the police another

volley of abuse.

'Sorry, Mamma,' he said, 'the butei [supporters] are making a bit of a

racket. We're just

leaving the station now, so if you put on the pasta round, what, 6.30,

I should be back when

it's cooked. Ciao, Mamma.'

That, in a nutshell, rather sums up Italy, a country where emotions are

turned on and off like

gas. Parks, however, is not an impartial observer, an anthropologist with

a government grant

sent to study the animals cavorting on the terracings. Unashamedly, he

is one of them, a

rabid, zealous convert to Verona's cause. Over the course of the year,

he religiously follows a

team whose only raison d'tre is survival. Come the end of the

season, they will not be

challenging the likes of Inter Milan or Juventus for a place in the Champions

League. The best

they can hope for is to avoid the drop into the dreaded Serie B -- purgatorio

-- which

would then allow the possibility of the unthinkable, a further descent

in the Serie C

inferno. Their aim is to remain in Serie A -- paradiso.

It all starts promisingly enough with a trip to Bari in the deep south

of the country. Parks

turns up at midnight at the Zanzibar, a cafŽ bar on the outskirts

of the town, for the

550-mile trip. Only the hardcore supporters, the brigate, are prepared

to make such a long

journey. Drugged and drunk, their obscenities word perfect despite the

summer hiatus, they

are literally fighting fit. Any sleep is out of the question. Such conversation

as there is on the

bus centres on the case of a man called Marsiglia, a Uruguayan Jew born

to Italian parents

who was fired from a local school claiming racism and alleging he had been

beaten up.

To the rest of the country, this confirms what they think of Verona and

its inhabitants. They

are incorrigibly racist, uncultured bigots, workaholics, crude and gross.

As Parks points out,

while the tourists ponder the splendour of 'one of the few places in the

world that has

managed to preserve the centuries-old elegance of an impeccable Renaissance

humanism',

everyone else has written off this part of the peninsula as 'a national

disgrace, a pocket of

the most loathsome and backward right-wing dogmatism.'

In part at least, the accusations can be explained by rabid local rivalries

which in a young

country like Italy are still intense. In part, too, they have a historical

basis. And in part,

there is no smoke without fire. But they are also, as Parks patiently explains,

a figment of a

biased media's imagination, a handy stereotype with which to beat one's

ancient enemies.

Unpicking Marsiglia's story, which the newspapers neglected to do when

it first surfaced, it is

revealed that his account is seriously flawed. He has invented his persecution

to divert

attention from his lack of qualifications.

But to the regulars of the curva, Verona's equivalent of the Kop, the story

is merely a

diversion from the main attraction. To these people, whose lives are measured

out in the

weekly results, the performance of their team of hasbeens and wannabes

is everything: life,

death and bottles of potent limoncello.

To the brigate, Parks is known as parroco -- parish priest. To be given

a nickname, however

insulting, shows that after living in Italy for 20 years he is accepted.

It is a mark of respect;

now he is a fellow traveller, supporter and sufferer. And how Verona make

their fans suffer.

Their habit is to score early and hang on, a northern trait. In contrast,

southern teams such

as Lecce and Reggina only come to life late in the game. It is symbolic

of the country as a

whole, suggests Parks, almost convincingly.

As the season progresses, it looks as if Verona are heading for purgatorio.

They are in a

dogfight to avoid relegation. What makes it worse is that Chievo, with

whom they share a

ground, look as if they will be promoted from SŽrie B. Meanwhile,

the coach is reading

Ken Follett. For comfort or inspiration? Can things get any worse?

They can't get any more complicated, that's for sure. With one game of

the league left, any

one of five teams could be relegated. It's Judgement Day. All watches are

synchronised to

ensure all games start at the same time to ensure nobody has an unfair

advantage. Parks can

barely bear to watch. His enthusiasm and knowledge are conspicuous on every

page.

As the league progress he sucks us in, until -- absurdly -- we want at

the end to be with the

brigate, part of the collective outpouring of unadulterated emotion, as

they chant -- to the

tune of Guantanemera -- 'Non si capisce ma come parlate' ('We can't understand

what the f***

you're saying'). They are nutters and he's a nutter but, for 90 minutes,

anything goes. It's a

game of multiple epiphanies.

'Please don't write a sad book about football,' Verona's marketing man

implored Parks. He may

rest assured he hasn't.

|

THE

OBSERVER

One

of the pleasures of being a football fan is that it gives you a

faith. This is implicit in the word: 'fan' comes from the Latin

fanaticus, meaning 'a worshipper'. Your team is your god, and

on match-days you become a fundamentalist - you become

what Tim Parks calls 'a weekend Taliban'.

It's an alluringly uncomplicated faith, too. Cast in the Manichean

light of fandom, the world divides neatly in two: two halves, two

teams, two goals. Right and wrong are marvellously clarified; as

distinguishable as the colours of the players' shirts.

Tim Parks, who has been a fan of Hellas Verona for nearly 20

years, is contemporary English literature's Italian connection. He

lives with his Italian family in Verona, and he writes, translates

and broadcasts in both Italian and English.

In English alone, since 1997 he has published three collections

of essays, two novels - including the Booker-shortlisted Europa -

a travelogue, and three translated novels, as well as a torrent of

journalism. He seems able, as Martin Amis observed of the even

more prolific John Updike, to blurt out a book before breakfast.

In early 2000, Parks decided that he would travel to every Hellas

match in the upcoming season, home and away, and write

about his experiences (this is more of a time commitment than

it sounds: Italy is a long country).

With the aim of better understanding 'how people relate to

football... how they dream this dream at once so intense and so

utterly unimportant', he also decided to spend much of his

match-time with the self-styled brigate gialloblù - the

'yellow-and-blue brigade', the hardcore Verona fans who turn

matches into a 24-hour carnival of substance abuse, barracking,

and violence.

Parks would join the tribe, in other words: the anthropologist

would go native. A Season With Verona is the result of this total

immersion. There were 34 matches in the season, there are 34

chapters in the book. Each chapter combines an account of a

match with Parksian musings on crowd psychology, nationhood,

authority, influence and all the other ideas that make up the

myth of football.

After each chapter/match are printed the results of Serie A

across the board, and Verona's consequent position in the

league table. Quickly, even if you don't know anything about

Hellas, and even though the season in question wound up a year

ago, you start to care about what happens in the next game.

Almost irresistibly, you become a Hellas supporter.

In Serie A terms, Hellas are a struggling team. In 1985, 'the year

of the miracle', they won the scudetto, the league title. Since

then, however, they have been commuting back and forth

between Serie B and Serie A.

Failure is in its way as powerful a gelling agent as success, and

Hellas's sustained poor form partly explains why their fan-base

is renowned for being so tight-knit and so ultra - so extreme.

Hellas fans are the pariahs of Italian football, deplored

countrywide for their racism and vandalism. This antipathy

serves only to consolidate their group identity, however: the

brigate thrive on an inverted elitism, proud to be the worst of the

worst.

Parks admits early on in the book that the brigate are 'not a

savoury bunch'. Too right. They make monkey-noises whenever

a black opposition player touches the ball. They sing celebratory

songs about the Juventus supporters killed at Heysel. They

compose admiring hymns to murderers and serial rapists. The

question Parks wants to answer in his book is why? Why do

they do these things, when the team itself - composed of

imported players, none of whom is a native of Verona - is so

remote from their lives? Why does fandom activate such a

ferocious rush of feelings in people?

One answer, of course, is that it neuters boredom, that

definingly modern disorder. Being fanatical makes life interesting

again. Among the brigate boys we get to know is Forza, who

works with disabled children during the week, and then gets

pissed up, coked up and beaten up every match-day. He clearly

loves the elation of transgression (though he wouldn't call it

that): of having a weekend Hyde to his weekday Jekyll.

Another answer is that following a team offers what Parks calls

'the close ties of an undying community'; a pseudo-family. 'Can

we imagine a fan on his own?' Parks asks. No, of course not.

Fans only exist in the plural, unified by chant and slogan. Forza

and all the other feckless members of the brigate love being part

of a gang, a tribe, a crowd; they love being assimilated into a

whole.

Parks himself is to a degree assimilated by the brigate. In the

brilliant first chapter of the book, in which he describes travelling

by coach with the fans to see Hellas play Bari away, there is a

distinct gap between the mania of the fans, and Parks's

detached account of it (to pass time on the bus, he notes dryly,

'they insult the driver and then sing, mainly in praise of deviant

behaviour'). But as the season wears on, this gap narrows.

Parks starts to lose his moral perspective on the brigate 's

behaviour.

One moment exemplifies this. En route to an away game

against Napoli, the train stops briefly in Bologna. A brigate

member named Nato gets off, and first insults and then assaults

a man who is kissing his girlfriend goodbye on the platform. The

way Parks tells it, Nato is just a boy being a boy. He's not of

course: he's a thug who's ruined someone's life for a while.

Parks never loses his power elegantly to analyse the 'dream' of

football, but his power to criticise some of its collateral effects

does diminish.

This doesn't diminish the book; it makes it even more

interesting. A Season With Verona is addictive reading, for its

acute cultural criticism, for Parks's ability to evoke the 'choral

pandemonium' of live football, and for its brilliant narrative rhythm

- each chapter is a short story, the whole book an epic. With the

wind of the World Cup in its sails, this will undoubtedly and

deservedly be Parks's biggest success to date.

|

THE

SEATTLE TIMES

First, a disclaimer: I am not a soccer fan. To

my mind, the 90 minutes it takes to watch or

play a match is 90 minutes of my life I'll never

get back.

I am, however, a fan of Tim Parks, and would

willingly spend hours following him through the

most arcane minutiae of the Bulgarian tax code

if that's what he chose to write about. Since

Parks is the object of my literary affection, and

soccer is the subject of his latest book, "A

Season with Verona," it was inevitable I would

find myself reading about Italy's national

pastime; despite my utter indifference to the

sport, I even expected to enjoy the experience — Parks is, after all, a

master

essayist who combines a first-rate intellect with a coruscating prose style.

But what I never imagined possible was how completely I would end up

identifying with the fortunes of the team, Hellas Verona, and its obsessive,

foul-mouthed, occasionally violent, perennially disappointed but unflaggingly

loyal fan club, the Brigate Gialloblù.

Parks makes it clear early on that supporting Hellas

Verona is a masochistic endeavor from the get-go.

Describing a particularly painful moment of

reckoning when his team is down 3-1 against the

superior Parma team, he admits: "I have embarked,

over a period of some years now, in supporting a second-rate provincial

side, to

wit Hellas Verona F.C., something I am no doubt doing to satisfy all kinds

of

infantile dreams which hardly bear investigation. And now the side is letting

me

down. The boys are making a fool of me." Then, in a series of miraculous

plays,

Verona wins and he is hooked again.

As the season progresses, however, agony vastly outweighs ecstasy:

Players

are injured or sold; the coach is a disaster; the referees are biased;

worse

teams than Verona have better luck and midway through the year, it looks

like

Hellas Verona might slip from Series A competition to the purgatory of

Series B.

As Parks accompanies the increasingly despondent Brigate Gialloblù

to every

game, away and at home, his book alternates between white-knuckle

descriptions of particular matches (including the Brigate's bellicose antics),

and

more cerebral meditations on everything from politics to religion.

Parks, who has lived in Italy for more than 20 years, uses soccer to illuminate

the forces at play there: Scratch the surface of this modern nation and

you'll

discover a fractious collection of ancient city-states whose denizens identify

themselves not as Italian, but as Roman, Florentine, Milanese. Nowhere

is this

more apparent than in the soccer stadium, as the Brigate hurl invective

at the

opposition and receive it in return. Each insult is carefully crafted to

elicit

maximum outrage, drawing on whatever events, legends or characteristics

might

pertain to a particular town: in Vincenza they are magnagati — cat-eaters;

in

Turin, gobbi, or hunchbacks. The Brigate's epithets range from the offensive

to

the obscene — certainly you'll learn words here you don't find in the average

Italian/English phrase book.

Yet Parks manages to translate not only the sense of the words, but

the

sensibility that underlies them: To the boys of the Gialloblù, soccer

is serious

business, but they never forget that life itself is just a game.

But "A Season with Verona" is about much more than soccer. Parks himself

refers to it as a "travel book" — a bit of a misnomer unless one considers

"The

Divine Comedy" a travel book. One doesn't have to read far, however, before

it

begins to dawn that, like a modern-day Virgil, Parks is leading us on a

journey

that goes far beyond the fortunes of Hellas Verona and into universal issues

of

race, class, faith, patriotism, politics, identity, and yes, sport. When

it comes to

the passions that ignite us, he suggests, from Burma to Bogota, we are

all

Gialloblù.

|

THE

WASHINGTON POST

Every

sport gets the literature it deserves. Baseball gets the magic realism

of

W.P. Kinsella's Shoeless Joe and Bernard Malamud's The Natural.

Basketball, a game of superstars and individual artistry, lends itself

to the

self-centeredness of the memoir: Bill Bradley's Life on the Run, Wilt

Chamberlain's A View From Above. And football -- well, football has no

literature. The shelf of soccer books is not so long, either. But over

the years

it has become clear that the sport's ideal literary approach is something

like

the social realism of Zola.

This journalistic mode can capture the outrages of hooligans, the decrepitude

of skyboxless stadiums with the least sanitary bathrooms on the planet,

and

the brutal fouling on the pitch. No book embodies this spirit more perfectly

than Bill Buford's incredible 1992 account of English fandom gone awry,

Among the Thugs. And it is the spirit of dozens of other recent works,

including the novelist Tim Parks's nonfictional A Season With Verona.

Parks's book recounts a year spent with the brigate gialloblu (the

yellow-blue brigade), a particularly passionate fan club of the Italian

team

Hellas Verona. He picked his subject because he's lived in fair Verona

for

nearly two decades. But he also picked the brigate because it has achieved

infamy beyond the city's borders. The Italian press loves to depict its

members as the most racist, most violent fans on the continent.

In the course of a normal season, the brigate's antics make for compelling,

frightening narrative. They battle with police, make monkey noises when

black

players touch the ball, sing in praise of murder and rape and sexually

harass

every female in their path. But Parks lucked into an especially riveting

season

in which to hang around Hellas. Filled with has-beens and unformed youthful

talent, the team is bad, one of the worst in the league. And in European

soccer, the race to avoid being at the bottom is as intense as the race

to be at

the top: Every year the Italians banish the top-flight division's four

bottom

clubs to the Serie B -- equivalent to the minor leagues.

Describing life among these thugs, Parks's book attempts a surprising feat:

to

redeem the brigate from its critics. Amid his travels, he even becomes

one of

the hooligans himself. The brigate initiates him in its banter, calling

him

parocco, which means parish priest. In a way, the moniker fits perfectly:

Parks considers the brigate a religious community -- devoted, unable to

explain that devotion, lost in transcendent song. His admiration leads

him to

conclude that they don't really mean all those racist slurs. Indeed, they

are

subversives with a terrific sense of humor and an awareness of their

foolishness. "It is the liberal press they are against," he writes, "the

perennial

p.c. of contemporary society."

"The brigate are vocally racist," he argues, "mainly in order to prolong

a

quarrel with the pieties-that-be." It's not a very persuasive explanation

of their

vulgarity. (In fact, Parks goes overboard in their defense, referring to

"a

strange and exhilarating cocktail of theatrical transgression and studied

irony,

an intense sense of community always ready to defend itself with

self-parody"). But his empathy pays off. It allows him to turn the hooligans

into oddly likable, fully drawn characters. One of them works with disabled

children during the week. Others call their mothers on mobile phones,

moments after taunting immigrants.

In any event, it doesn't do justice to A Season With Verona to dwell on

Parks's portrayal of hooliganism. In every chapter, he digresses in strange

and

interesting directions. He untangles the confusing case of a Jewish

schoolteacher who claims to have been beaten by the brigate. He spends

a

chapter spinning a clever exegesis of a poem by the 19th-century writer

Giacomo Leopardi, explicating it as a theory of the soccer fan's passion.

Another section transfers the insights of early 20th-century anthropology

to

the chauvinism of an ethnically homogeneous city like Verona. Indeed, Parks

is strongest when he acts as anthropologist himself, explaining the Italians

he

has lived among for so many years -- their constant sense of grievance,

their

patience with bureaucracy, their conspiracies.

There is another profound anthropological truth in Parks's book. He succeeds

in explaining the passion of soccer so evident in recent images of the

World

Cup -- Russian fans overturning cars in the shadow of the Kremlin and

distraught Argentinians crying into their beer. He shows that soccer thrives

as

sport for precisely the same reason that it succeeds as social realism:

its dark,

violent side. In his season with Verona, we see soccer unleash frightening

passion, because it yields better villains than any the World Wrestling

Federation has concocted and more wrenching plot twists than a Jerry

Bruckheimer movie. In other words, he inadvertantly rebuts soccer's critics

on

this side of the Atlantic and shows it to be all-American game.

|